In part 1 of our discussion on NSAIDs, we discussed the equal efficacy of various NSAIDs, while in part 2, we looked at the concept of an analgesic ceiling effect when using NSAIDs.

Congrats to all of those who identified the ceiling in part 2 as the Chihuly work at the Bellagio in Las Vegas. Damon Tedford (@DamonTedford) wins the sammich for being the first to get the correct answer.

Today we’ll look at the side effect profiles of different NSAIDs. While all NSAIDs are created equal with regards to analgesia, this is not the case for their side effect profiles. Some NSAIDs are definitely more toxic than others.

While NSAIDs are a great bunch of analgesics, they unfortunately have GI, renal, and cardiac side effects. For young, healthy patients, the upper GI complications (UGICs) are the most common side effect, as their renal/cardio complications are better tolerated. In the over 60 population, those with pre-existing cardiac/renal disease, and a few other groups, the renal and cardiac complications are also often seen.

So which NSAIDs are most dangerous?

P. terribilis (No joke, it’s actual species name is terribilis)

P. terribilis (No joke, it’s actual species name is terribilis)

If this frog were an NSAID, which one would it be?

If you guessed ketorolac, nice work.

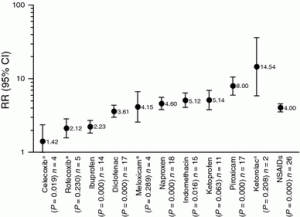

This 2010 systematic review looks at the relative risk for upper GI bleeding/perforation for both traditional and non-traditional (ie: coxib) NSAIDs. It should be noted that NSAIDs increase the risk of lower GI bleeding as well, despite UGICs being most commonly discussed in the literature.

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00296-011-2263-6/fulltext.html

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00296-011-2263-6/fulltext.html

As you can see, the traditional NSAIDs fall into 3 rough categories for UGIG: low-risk, intermediate risk and high-risk. (Pooled RRs in parentheses)

Low risk

Ibuprofen (2.23)

Intermediate risk

Diclofenac (3.61)

Naproxen (4.6)

Indomethacin (5.12)

High risk

Ketorolac (14.54)

In addition to being no better for pain, ketorolac is also way nastier than other NSAIDs. Depending upon the paper you read, you’ll find slightly different numbers, but the relative risk of traditional NSAIDs will pretty much always fall into these 3 groups.

An important caveat to these numbers is that they are pooled RRs between low dose and high dose NSAIDs. All NSAIDs have much greater toxicity at higher doses.

Here is an example from a paper looking at UGICs with traditional NSAIDs.

The odds ratios for UGICs with Ibuprofen at:

Dose (mg/day) OR:

<1200 1.1 (95% CI 0.6-2.0)

1200-1799 1.8 (0.8-3.7)

>1800 4.6 (0.9-22.3)

Thus, 400 mg QID and 600 mg QID of ibuprofen have the same analgesic effect, but a total daily dose of 2400 mg is associated with more side effects than 1600 mg.

With ketorolac, risk similarly increases, but the complication rate is already so high (RR 20 at <20 mg/day) in (*edit: this 1998 study), why would you even want to prescribe it in the first place. For those wondering about risk when given parenterally, the RR for IM ketorolac is even greater than PO (28.3 vs. 20) in the same study.

So who will get the bleed? In this great 2012 review article from Conaghan, the risk factors for UGIC are:

*Elderly (Age >60)

*History of PUD (especially if complicated by bleed/perforation)

*Multiple NSAID use

Concomitant ASA, steroids, anticoagulants or SSRIs

Concurrent H. pylori infection

Smoking

*denotes major risk factor

But I want to prescribe my patient some NSAIDs for their pain. Can I prevent these side effects?

Fortunately you can. Both misoprostol and PPIs will significantly reduce side effects of traditional NSAIDs, while H2 blockers will not. This has been studied in the ARAMIS cohort study, where it was found that the RR for UGICs when misoprostol or omeprazole was added was 0.6, while the RR was 1.4 with H2 blockers.

Bottom line:

Different NSAIDs all produce similar levels of analgesia, but some are much worse than others when it comes to side effects. There is no need to prescribe NSAIDs above their dose ceiling, as it endangers the patient without providing any benefit. Be aware of risk factors for UGICs (esp. age >60, previous ulcer and multiple NSAIDs) and always consider prescribing a PPI when giving out an NSAID.

Cheers,

Chris

@SocmobEM

Post written by Chris Bond and peer reviewed by Nadim Lalani (@ermentor) and Brent Thoma (@boringem).

References

ARAMIS Study: Singh G Am J Ther. 2000 Mar;7(2):115-21.

García Rodríguez LA1, Cattaruzzi C, Troncon MG, Agostinis L. Risk of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with ketorolac, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, calcium antagonists, and other antihypertensive drugs. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Jan 12;158(1):33-9.

Conaghan PG, Rheumatol Int. 2012 Jun;32(6):1491-502. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2263-6. Epub 2011 Dec 23. Review.

Lewis, S. C., Langman, M. J. S., Laporte, J.-R., Matthews, J. N. S., Rawlins, M. D. and Wiholm, B.-E. (2002), Dose–response relationships between individual nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NANSAIDs) and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis based on individual patient data. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 54: 320–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01636.x

Massó González, E. L., Patrignani, P., Tacconelli, S. and Rodríguez, L. A. G. (2010), Variability among nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 62: 1592–1601. doi: 10.1002/art.27412

Leave a Reply